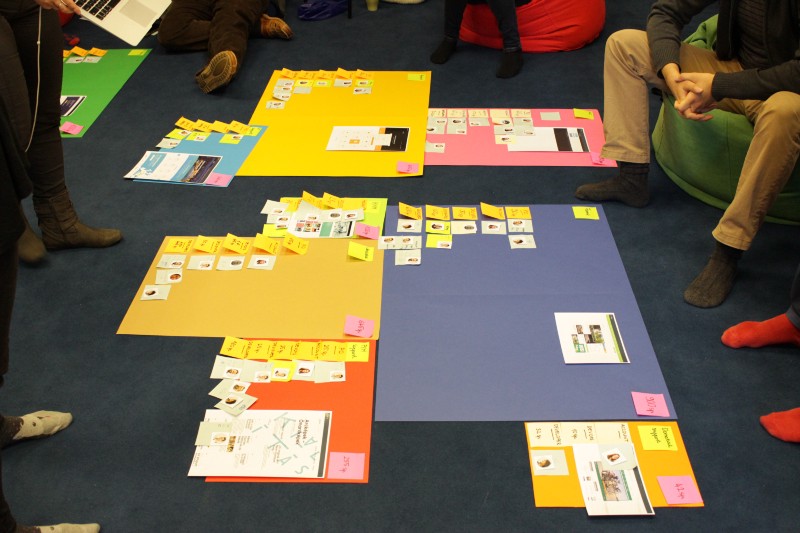

I advertised my products as a market stall. Come, come! Only 300 points to go! Eighty, forty, sold out! The guys went around with a printed replica of their faces and a marker pen to add themselves to the projects they'd like to work on.

If you have 500 credits for the next quarter, how would you divide them between your projects? The idea of the zero-sum game is to let everyone decide their fate by optimally spreading their desires and competencies.

The company's client contacts have written the contractual commitments on each product: for this development, we have contracted for 800 points, for another, we have acquired for 1000 points, and for the third, we have to support the product with 240 points.

Say another?

In some ways, it's easier if someone else tells you what you need to do next. If the project manager, project host, boss, or whoever tells you what to do, lets you know when and what is expected of you, and dictates how you should do it, you don't have to think too hard. You have the issue-stream, then you can push it as far as you can down the tube. Sometimes it all goes like clockwork; other times, you're on a tight deadline, but there's always going to be a distraction in the force. Your supervisor will pocket your successes, and failures will be generously thrust upon you along with the tasks. And not even out of malice. Kahneman has examined the psychological biases that influence these and other decisions. He was awarded the Nobel Prize.

What did we get out of this?

We iterated through the process for about an hour until we were within the margin of error for the proportion of points we could allocate. So we could see what proportion of the projects each of us wanted to work on, but the hard part was still to come. How can we shape the teams so that the seventeen projects in the pipeline are distributed proportionally between them?

We started to organize the work into groups based on the commitments indicated. After some agonizing, it turned out that the previous set-up had been modified somewhat, but overall the new situation did not seem any better. The workshop had been going on for three hours; everyone was tired and hungry when someone asked the question: what was the point of everything if there was no substantive change?

We were at the nadir of democratic organization. We have been in this situation countless times in the seven years we have been playing the game of evolutionary organizational development. The problem is that the most difficult burden of human-centered functioning is decision-making. It is slow and often conflictual because a consensus direction has to emerge from a confluence of many viewpoints, which often seems no better than what the leader could have said on their own.

Then, just as we were about to fall on the sword, Zoli spoke up, and all his words were right:

"Today's workshop was not about big change. It was a space to take individual responsibility for the next quarter. That's all that happened, nothing more."

Share with your friends!